The Art Of Failure Of course. “The Art of Failure” is a rich and paradoxical concept. It can be approached from psychological, philosophical, and practical angles. Here is a detailed exploration of its meaning and principles.

The Core Paradox: What is “The Art of Failure”?

- At its heart, “The Art of Failure” is the practice of reframing our relationship with failure. It is not about aiming to fail, but about extracting value, wisdom, and growth from the inevitable experience of not succeeding. It transforms failure from a mark of shame into a necessary and instructive part of the journey toward mastery, innovation, and resilience.

- The “art” lies in how we respond: our ability to analyze, learn, and persevere.

The Pillars of the Art of Failure

1. The Psychological Shift: From Fixed to Growth Mindset

- Psychologist Carol Dweck’s research is foundational here.

- Fixed Mindset: Sees failure as a verdict on one’s inherent ability. (“I’m just not good at this.”) This leads to avoiding challenges and giving up easily.

- Growth Mindset: Sees failure as data. (“What can this teach me? What should I try differently?”)

- The Art of Failure requires cultivating a growth mindset.

The Scientific Principle: Trial, Error, and Iteration

All progress in science and technology is built on failure.

- The Scientific Method: A hypothesis is an “educated guess” that is tested. A failed experiment is not a waste; it’s a crucial data point that narrows down the possibilities and leads to a better hypothesis.

The Philosophical Acceptance: Stoicism and Resilience

- Stoic philosophy teaches us to focus on what we can control and accept what we cannot.

- You cannot control the outcome. You can only control your effort, your preparation, and your reaction to the result.

- Failure, then, is an “external.” It is not inherently good or bad; its value is determined by our judgment of it. The art is in accepting the outcome without letting it diminish your self-worth or determination.

The Creative Process: Breaking and Remaking

- Artists, writers, and musicians understand that the first draft, the first sketch, is often a “beautiful failure.”

- It contains the raw material but needs refinement. The creative process is one of constant revision—a series of small failures that lead to a stronger final product.

- J.K. Rowling’s initial rejections for Harry Potter are a classic example. The failure to get published wasn’t the end; it was part of the story.

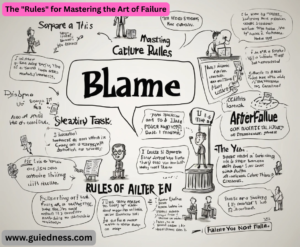

The “Rules” for Mastering the Art of Failure

Mastering this art is an active practice. Here’s how to do it:

- Separate Your Identity from the Outcome: You are not your failure. Instead of thinking “I am a failure,” reframe it to “I failed at this specific task.” This creates the psychological space needed to learn.

- Conduct a Post-Mortem Without Blame: After a setback, analyze it dispassionately.

What went wrong? (Process, not person)

- What assumptions were incorrect? What could be done differently next time? What did I learn about the problem, the world, and myself?

- Embrace “Intelligent Failure”: Not all failure is equal. Harvard Business School professor Amy Edmondson distinguishes between:

- Praiseworthy Failures: Those that occur in pursuit of a goal, in new territory, and from which we can learn. (e.g., a bold experiment that doesn’t pan out).

- Blameworthy Failures: Those resulting from negligence, deviation from a known process, or a lack of effort.

- Start Small and Build Resilience: Practice failing in low-stakes environments. Try a new hobby you’ll likely be bad at initially. Speak up in a meeting with a risky idea. This builds the “muscle memory” for handling larger setbacks.

- Normalize It: Share your failures openly. When leaders and peers talk about their own mistakes, it creates a culture where learning is valued over the illusion of perfection. This is crucial for innovation in teams and organizations.

The Dangers of Not Practicing the Art of Failure

- If we don’t learn this art, we fall into predictable traps:

- Perfectionism: Paralysis by analysis, never shipping the product, never finishing the novel.

- Risk-Aversion: Sticking to the safe and familiar, leading to stagnation.

- Fragile Ego: An inability to handle criticism or feedback.

- Missed Learning Opportunities: Each failure is a lesson left unlearned.

Advanced Dimensions of the Art

The Antifragile Dimension: Beyond Resilience

- Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s concept of Antifragility takes the art of failure a step further.

- Fragile: Breaks under stress and volatility (e.g., a wine glass).

- Robust/Resilient: Withstands stress and remains the same (e.g., a rock).

- Antifragile: Gains from stress, disorder, and shocks (e.g., the immune system, muscle growth, innovation).

- The ultimate art of failure is to create systems—and a personal mindset—that are antifragile. You don’t just “bounce back” from failure; you emerge stronger, wiser, and more capable because of it. A startup that survives a market crash learns invaluable lessons its competitors didn’t. A writer whose first book is criticized harshly can use that feedback to write a masterpiece.

. The Paradox of Aiming to Fail

- This is the most counterintuitive aspect of the art. In certain contexts, you must actively seek out failure to achieve ultimate success.

- In Learning: If you are not failing at least 15-30% of the time, you are not operating at the edge of your capabilities. You’re in your “comfort zone.” To learn a language, you must speak it poorly and make mistakes. To master a sport, you must attempt plays that are currently beyond your skill.

- In Innovation: Companies like Amazon and Google institutionalize this. They launch countless projects (like Amazon’s Fire Phone) expecting many to fail. The goal is to “fail fast, fail cheap,” and use the lessons to fuel the few massive successes (like AWS) that pay for everything else.

The Emotional Alchemy: Processing Shame and Disappointment

- The intellectual understanding of failure is easy. The emotional toll is the real work. The art lies in alchemizing painful emotions into fuel.

- Shame → Accountability: Instead of “I am bad,” shift to “I am responsible for fixing this.”

- Disappointment → Refined Expectation: Instead of despair, use disappointment to calibrate a more realistic and strategic plan for the next attempt.

- Fear → Focus: The fear of future failure can be harnessed as intense focus on preparation and detail.

To truly understand the Art of Failure,

- we must also recognize its cunning opposites—the strategies we use to avoid the sting of failure, which ultimately hold us back. These are the “unarts.”

- The Art of Procrastination: Delaying a task to avoid the potential failure of doing it poorly. The temporary relief of avoidance is a poor substitute for the growth of attempting.

- The Art of the Safe Bet: Only pursuing goals with a near-guaranteed chance of success. This leads to a life of “what ifs” and quiet regret.

- The Art of Excuse-Making: Developing elaborate, plausible-sounding reasons for why something didn’t work out, deflecting blame from oneself. This destroys any chance of learning.

- The Art of Perfectionism: Hiding behind the endless pursuit of perfection to avoid ever submitting your work to judgment. An unfinished masterpiece cannot fail, but it also cannot succeed.

- Mastering the true Art of Failure requires consciously dismantling these “unarts.”The Neurobiology of Failure: What Happens in Your Brain When You Fail

Understanding the physical reaction demystifies the emotional pain and allows for better management. - The Threat Response: Failure is often processed by the brain as a social threat, similar to physical pain. The anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), which registers pain, lights up. This is why failure can feel physically painful—it’s not just in your head, it’s from your head.

- The Amygdala’s Alarm: The amygdala, our threat-detection center, can become hyperactive, triggering a fight-or–flight response (anxiety, anger, avoidance). This is the biological root of the urge to give up or blame others.

- The Learning Opportunity (IF you seize it): After the initial shock, if you engage in analytical thinking—”Why did this happen?”—you activate the prefrontal cortex (PFC). The PFC can regulate the amygdala’s panic and turn the event into a learning experience. This is the neurological basis of the “post-mortem.”

- The Art, therefore, is to consciously engage the PFC to override the amygdala’s alarm. This can be done through mindfulness, journaling, or simply taking a deliberate pause before reacting.