Sustainable Agriculture Practice Of course. Here is a comprehensive overview of sustainable agriculture practices, explaining what they are, why they matter, and detailing key methods.

What is Sustainable Agriculture?

It’s built on three core pillars:

- Environmental Health: It seeks to safeguard soil, water, and air quality, and promote biodiversity.

- Economic Profitability: Farms must be financially viable to continue operating and supporting families and communities.

- Social and Economic Equity: It treats farmworkers fairly, supports rural communities, and provides consumers with healthy, accessible food.

Why is it Important? The Challenges of Conventional Agriculture

- Conventional, industrial-scale agriculture has often prioritized high yields and short-term profits, leading to significant problems:

- Soil Degradation: Tilling and monocropping deplete organic matter, leading to erosion and loss of fertile topsoil.

- Water Pollution & Scarcity: Runoff from synthetic fertilizers and pesticides contaminates waterways. Irrigation can deplete aquifers.

- Loss of Biodiversity: Large fields of a single crop create “green deserts” that don’t support other plant, insect, or animal life.

- Greenhouse Gas Emissions: Contributes significantly to emissions through fossil fuel use, methane from livestock, and nitrous oxide from fertilizers.

- Economic Pressure on Farmers: High costs of inputs (seeds, fertilizers, chemicals) and volatile market prices can make farming

economically unstable.

- Sustainable practices directly address these challenges.

Key Sustainable Agriculture Practices

- These practices are often used in combination to create a resilient farming system.

Soil Health Management

Healthy soil is the foundation of a sustainable farm.

- They prevent erosion, suppress weeds, and add organic matter and nutrients (like nitrogen) to the soil when tilled under.

- Composting and Manure Management: Recycling organic waste into nutrient-rich compost reduces the need for synthetic fertilizers and

improves soil structure.

- This breaks pest and disease cycles and improves soil fertility (e.g., rotating nitrogen-fixing legumes with nitrogen-consuming corn).

Water Management

- Sustainable Agriculture Practice Drip Irrigation: Delivering water directly to the base of the plant through tubes or tapes.

- Rainwater Harvesting: Collecting and storing rainwater from barn roofs and other surfaces for irrigation.

- Soil Moisture Monitoring: Using sensors to water crops only when necessary, avoiding waste.

- Drought-Tolerant Crops: Choosing crop varieties that are naturally adapted to require less water.

Biodiversity & Ecosystem Integration

- Polyculture & Intercropping: Growing multiple crop species together in the same field. This mimics natural ecosystems, reduces pest outbreaks, and can improve yields.

- Trees can provide windbreaks, shade, fruit, and habitat for beneficial species.

- This includes introducing beneficial insects (biological control), using traps (monitoring), planting pest-resistant varieties, and only using

pesticides as a last resort.

- Conservation of Natural Areas: Leaving field borders, wetlands, and forests untouched provides crucial habitat for pollinators, birds, and other wildlife that contribute to a healthy farm ecosystem.

Animal Integration and Welfare

- Sustainable Agriculture Practice Managed Grazing & Rotational Grazing: Moving livestock frequently between pastures. This prevents overgrazing, allows vegetation to recover, and evenly distributes nutrient-rich manure, improving pasture health.

- Pasture-Raised Livestock: Allowing animals to graze on open pasture is more humane and improves their health, reducing the need for antibiotics. Their manure also naturally fertilizes the land.

- Mixed Crop-Livestock Systems: Combining crop and animal production on the same farm creates a closed-loop system where animal waste

fertilizes crops, and crop residues can feed animals.

Socio-Economic Practices

- Direct-to-Consumer Sales: Selling through farmers’ markets, Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) programs, or farm stands keeps more profit in the farmer’s pocket and builds community connections.

- Fair Labor Practices: Providing safe working conditions and fair wages for farmworkers.

- Energy Efficiency: Using renewable energy (solar, wind, biodiesel) to power operations and adopting energy-saving technologies.

- A Real-World Example: The Sustainable Farm Cycle

A sustainable farmer might:

- Rotate a field of corn one year with soybeans (a legume that adds nitrogen) the next.

- After harvest, plant a cover crop of winter rye to hold the soil in place.

- Use no-till methods to plant the next season’s crop directly into the cover crop residue.

- Integrate chickens into the crop rotation; after harvest, they are allowed to graze the field, eating leftover grains and insects while

fertilizing the soil with their manure.

- Use IPM by planting wildflower borders to attract beneficial insects that prey on crop pests, only spraying a targeted pesticide if an outbreak occurs.

- Sell the harvest at a local farmers’ market, creating a direct relationship with customers.

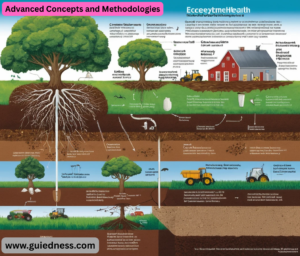

Advanced Concepts and Methodologies

- Sustainable Agriculture Practice Several frameworks fall under the sustainable agriculture umbrella, each with a slightly different emphasis:

- Regenerative Agriculture: This goes a step beyond “sustainability” (maintaining resources) to actively improve and restore the ecosystem. The primary focus is on rebuilding soil organic matter and restoring degraded soil biodiversity. The key outcomes are carbon sequestration (drawing down atmospheric carbon into the soil), increased water retention, and enhanced ecosystem health. It’s often seen as a powerful

tool in the fight against climate change.

- Agroecology: This is the application of ecological concepts to agricultural systems. It emphasizes the relationships between plants, animals, humans, and the environment within agricultural systems. It’s not just a set of practices; it’s a scientific discipline, a social movement, and a practice. It strongly focuses on local knowledge, farmer-to-farmer networks, and food sovereignty.

- Permaculture: A design system for creating sustainable human habitats by following nature’s patterns. It involves thoughtfully designing the landscape to mimic the relationships found in natural ecosystems, integrating water catchment, perennial plants, animals, and energy systems to create a self-

sustaining and highly productive “food forest.”

- Sustainable Agriculture Practice Organic Farming: A legally defined and certified system that primarily restricts the use of synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, genetically modified organisms (GMOs), and antibiotics. While organic practices are a huge part of sustainability, organic certification doesn’t always encompass the full socio-economic and holistic land management principles of other frameworks.

The Role of Technology (AgTech for Sustainability)

- Modern technology is a powerful ally in making sustainable practices more efficient and scalable.

- Precision Agriculture: Using GPS, sensors, and data analytics to apply water, fertilizers, and pesticides with extreme precision. This means a tractor can apply different amounts of inputs to different parts of a field based on real-time needs, drastically reducing waste and environmental impact.

- Satellite and Drone Imagery: Provides farmers with a macro-view of their fields, helping them identify areas of stress (pests, drought, nutrient deficiency)

early on, allowing for targeted interventions.

- Internet of Things (IoT): Soil moisture sensors can automatically tell irrigation systems when and where to water. Smart weather stations provide hyper-local data.

- Biologicals: A cutting-edge area involving biopesticides (derived from natural materials like plants, bacteria, and minerals) and biofertilizers (microbes that fix nitrogen or make soil nutrients more available to plants), reducing reliance on synthetic chemicals.

Challenges and Criticisms

Transitioning to sustainable agriculture is not without its hurdles:

- Knowledge & Transition Period: Shifting from conventional methods requires new knowledge and skills. There can be a financial dip during the transition

- period as soil health rebuilds and new systems are established.

- Scalability & Yield Debate: A persistent criticism is whether sustainable methods can produce enough yield to feed the global population. Proponents argue that while some yields may be lower initially, they become more stable and resilient over time, especially in the face of climate extremes. The focus shifts from yield per acre to profit per acre and nutrition per acre.

- Labor Intensity: Some practices, like detailed crop rotation or manual weeding in organic systems, can be more labor-intensive than conventional monocropping with herbicides.

- Market Access & Consumer Cost: Sustainable food products often cost more due to higher labor costs and the true cost of production being factored in. This can limit access for lower-income consumers.