Problem solving Of course! Problem-solving is a fundamental skill in life, work, and everything in between. It’s a structured process for moving from a problem to a solution. Here is a comprehensive guide to effective problem-solving, broken down into a clear framework, methods, and tips.

The Universal Problem-Solving Framework

- This is a 5-step cycle that can be applied to almost any problem, from a broken-down car to a complex business challenge.

Step 1: Define and Understand the Problem

- You can’t solve a problem you don’t understand. This is the most critical step.

Ask “What, Why, Who, When?”:

- What is the specific problem? (Be precise. “Sales are down” is vague. “Sales in the European region have dropped 15% in Q2 compared to Q1″ is specific.)

- Why is it a problem? (What is the impact? “This puts us at risk of missing our quarterly revenue target.”)

- Who is involved or affected? (The European sales team, customers, the marketing department.)

- When did it start and when does it need to be solved? (Started in April, needs a solution before the end of July.)

- Rephrase the Problem: State the problem in your own words. This forces clarity.

- Identify the Root Cause: Don’t just address symptoms. Use the 5 Whys Technique: Ask “Why?” repeatedly until you find the core issue.

Problem: The website is crashing.

- Why? Server CPU is at 100%. Why? A new feature’s code is inefficient. Why? It wasn’t properly load-tested before launch.

Why? We rushed the release to meet a deadline.

- Why? We don’t have a robust testing protocol for rushed releases. (Root Cause)

Step 2: Generate Potential Solutions (Brainstorming)

- At this stage, focus on quantity over quality. The goal is to create a wide range of options.

- Defer Judgment: No idea is a bad idea during a brainstorm. Critiquing too early kills creativity.

- Aim for Variety: Think of obvious solutions, creative solutions, and even “crazy” ones that might spark a practical idea.

Use Techniques:

- Mind Mapping: Start with the core problem and branch out with related ideas.

- SCAMPER: A checklist for ideas: Substitute, Combine, Adapt, Modify, Put to another use, Eliminate, Reverse.

Step 3: Evaluate Options and Select the Best One

Now, analyze the list of potential solutions from Step 2.

- List Pros and Cons: For each promising solution, write down the advantages and disadvantages.

- Use a Decision Matrix: For more complex decisions, create a grid. List your solutions as rows and your key criteria (e.g., Cost, Time, Effectiveness, Risk) as columns. Score each solution (e.g., 1-5) on each criterion. The solution with the highest total score is often the most balanced choice.

- Consider Feasibility: Is the solution practical? Do we have the resources (time, money, people)?

- Assess Risks: What could go wrong? Is the potential downside acceptable?

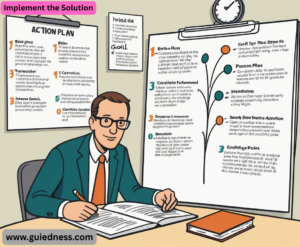

Implement the Solution

This is where you turn the plan into action.

- Create an Action Plan: Break the solution down into small, manageable steps. Use the SMART goal framework:

Specific: What exactly will be done?

- Measurable: How will you track progress? Achievable: Is the step realistic? Relevant: Does it directly contribute to the solution?

Time-bound: When will it be completed?

Assign Responsibilities: Who is responsible for each task?

- Allocate Resources: Ensure the team has what they need to succeed.

Step 5: Monitor, Review, and Adjust

The process doesn’t end once the solution is implemented.

- Measure Results: Check the metrics you defined in Step 1. Is the problem being solved? Are sales going back up?

- Get Feedback: Talk to the people involved. Is the solution working on the ground?

- Be Ready to Adapt: If the solution isn’t working as expected, don’t be afraid to go back to a previous step. Maybe you need a different solution (Step 3) or you misunderstood the problem (Step 1).

Helpful Problem-Solving Methods

Different problems require different tools.

- PDCA Cycle (Plan-Do-Check-Act): A continuous improvement loop, perfect for refining processes.

Plan a change.

Do implement it on a small scale. Check the results.

- Act on what you learned (standardize the change or start a new cycle).

- Divide and Conquer: Break a massive, complex problem into smaller, more manageable sub-problems. Solve them one at a time. (Essential in computer science and project management).

- Analogical Reasoning: Look for a similar problem that has been solved before, in a different context, and see if you can adapt that solution. (“How is this like…?”)

How to Improve Your Problem-Solving Skills

- Practice Consciously: Treat small, daily frustrations as practice problems. Use the framework to decide what to make for dinner or plan your commute.

- Learn from Others: Study case studies in your field. Watch how experts in your industry tackle challenges.

- Develop a Growth Mindset: Believe that your abilities can be developed through dedication and hard work. See problems as puzzles to be solved, not insurmountable obstacles.

- Broaden Your Knowledge: The more you know about different subjects (history, psychology, science, art), the more “mental models” you have to draw upon for creative solutions.

- Collaborate: Diverse perspectives almost always lead to better problem definition and more innovative solutions.

Example: Applying the Framework

- Problem: “I’m always late for work.”Step 1: Define

- What? I am late 2-3 times a week by 10-15 minutes.

- Why? My boss is getting annoyed, and I’m missing important morning updates.

- When? It started about a month ago when my morning routine changed.

Root Cause (5 Whys):

- Why? I leave the house too late. Why? I can’t find my keys/wallet/phone. Why? I don’t put them in the same place every night.

- Why? I’m tired and just drop them when I get home. (Root Cause)

Step 2: Generate Solutions

- Put a bowl by the front door for keys/wallet. Go to bed 30 minutes earlier to be less tired. Set a “leave the house” alarm on my phone.

Pack my bag and lay out my clothes the night before.

Advanced Problem-Solving Concepts

A. Problem Identification: It’s Harder Than It Looks

- Often, we jump to solutions for the symptom, not the real problem. Advanced problem-solving starts with precise problem identification.

Problem vs Symptom vs Solution:

- Symptom: “The car won’t start.” (This is what you see).

- Solution: “Jump-start the car.” (This addresses the problem).

- Root Cause: “The alternator is broken and not charging the battery.” (This is the underlying system failure that caused the problem).

- The Power of “How Might We…?” (HMW) Statements: Reframe the problem as an opportunity. This opens up creative thinking.

- Bad Framing: “How do we stop customers from complaining?”

- Bad Framing: “How do we make our team stop missing deadlines?”

- Good HMW: “How might we create a workflow where deadlines are realistic and easy to meet?”

Mental Models: Your Lenses for Seeing Problems

- First Principles Thinking: Boiling a problem down to its most fundamental, undeniable truths and reasoning up from there. Instead of assuming “this is how it’s always been done,” you ask, “What is objectively true?”

Example: Elon Musk used this to reduce the cost of rocket parts. Instead of buying expensive finished parts, he asked what the raw materials (aluminum, titanium, etc.) cost and figured out how to build them himself.

- Inversion: Thinking about a problem backwards or considering the opposite of what you want.

Instead of: “How do we achieve success?”

- Ask: “What would guarantee failure?” Then, make sure you avoid those things.

- First-Order Effect: “If we cut prices, sales will go up.” (Good).

- Second-Order Effect: “Competitors might cut their prices too, starting a price war that hurts everyone’s profits.” (Bad).

- Occam’s Razor: When faced with competing explanations, the simplest one is most likely to be true. (Don’t overcomplicate it).

- (Helps solve interpersonal problems by reducing bias).

. Overcoming Psychological Barriers (Why Smart People Get Stuck)

Our brains have built-in biases that hinder effective problem-solving.

- Functional Fixedness: The inability to see that an object can be used for something other than its traditional purpose. (e.g., Seeing a paperclip only for holding papers, not as a makeshift hook or tool).

- Confirmation Bias: The tendency to search for, interpret, and recall information that confirms our pre-existing beliefs. We actively ignore evidence that contradicts our initial hypothesis about the problem.

- The Einstellung Effect: The tendency to use a solution that has worked in the past, even if a better, simpler one exists. You get “stuck in a rut” of thinking.

- Anchoring: Relying too heavily on the first piece of information you receive. (e.g., The initial price offered sets the stage for all subsequent negotiations).

How to Combat These Barriers:

- Seek Disconfirming Evidence: Actively try to prove yourself wrong.

- Solo brainstorming often yields more diverse ideas.